The historic migration of the Yorubas of Ghana from Nigeria

The historic migration of the Yoruba people from Ile-Ife has shaped Ghana’s Yoruba community through trade, faith, and family ties. At the heart of this connection is Chief Brimah, an Ilorin merchant, whose leadership and entrepreneurial spirit forged enduring bonds with the Ga people and deeply influenced Accra’s Zongo communities.

In February 2022, following his enstoolment, the Ga Mantse, King Tackie Teiko Tsuru II went on a historic journey to Ile-Ife, Nigeria, the ancestral homeland of the Ga people, to reaffirm the cultural ties between the Ga and Yoruba peoples. Accompanied by a delegation of Ga traditional leaders, he was warmly received by the Ooni of Ife, Oba Adeyeye Enitan Ogunwusi Ojaja II, who had previously visited Ghana in 2016 to highlight the two groups’ shared kinship. These visits point to the mutual historical acknowledgement and the significance of their heritage in contemporary times.

Migration has long been a defining element of human history—shaping societies, economies, and cultures across the globe. In Africa, such movements have been instrumental in knitting together diverse cultures, histories, and traditions. For the Yorubas, whose ancestral lands span across Nigeria, Benin Republic and Togo, migration is integral to their identity. Their movements have connected disparate cultures and reshaped social landscapes.

As of 2024, the Yoruba population is estimated to be over 50 million in West Africa, with the majority living in Nigeria, Benin Republic, Togo and Ghana. Historically, African migrations were motivated by the need for fertile land, commercial possibilities, political struggle, religious expansion and even divination by soothsayers, as attested by oral tales of groups travelling in quest of better chances or to complete spiritual mandates. For example, Yoruba migrations frequently include these causes, resulting in vibrant trade and cultural interaction across regions.

These movements motivated interactions that created dynamic societies. A notable example is the shared histories of the Yoruba people of Nigeria and the Ga people of Ghana. It is believed that the Ga people emigrated from Ile-Ife in southwestern Nigeria before settling along Ghana’s southeastern coast.

Early migrations and shared heritage of the Yorubas and Ga

Oral traditions hold that the Ga trace their ancestry to Ile-Ife in Osun State, Nigeria. Some accounts suggest the Ga people emigrated from Ile-Ife around the 16th century, while some Ga oral histories maintain that they merely settled in Ile Ife for about 200 years on their way from Israel, before continuing their journey towards Accra. Another narrative links their migration to Benin in Edo State, Nigeria. Regardless of the Ga’s precise origin, the story that has prevailed and created a sense of shared heritage is one of Ga-Yoruba relations.

The Ga Mantse’s 2022 visit to Ile-Ife remains a landmark event in reconnecting historical bonds. Another notable moment occurred in December 2024, when the Ga Mantse hosted Olori Temitope Morenike Enitan-Ogunwusi, a wife of the Ooni of Ife, at his palace in Bukom. These engagements have strengthened the mutual respect and collaboration between the two groups in contemporary times. The Ile-Ife origin story would later set the stage for how Yoruba newcomers were received in Accra centuries later.

The journey of Chief Brimah and kolanut trade

The migration of Chief Brimah would bring a new chapter to the Ga-Yoruba shared narrative. Originally from Ilorin, a city with rich Yoruba and Fulani heritage, Chief Brimah’s sojourn to Accra stamped itself in history over 200 years ago, in the latter parts of the 1800s. This would mark the beginning of a Yoruba settlement in Ghana, establishing a new history of Yoruba-Ghanian heritage, and establish the Zongos that brought the influx of a mixture of Yoruba, Fulani, Nigér, and Hausa migrants under one umbrella.

According to oral histories, Chief Brimah’s migration was motivated by two speculative stories. One suggests that the political turmoil following the fall of the Oyo Empire and subsequent Fulani religious and political incursions into Ilorin in 1810 compelled him to seek safety elsewhere in the latter parts of the 19th century. Another narrative suggests that his Muslim cleric advised him through divination to move to a coastal area—a directive that led him to Accra.

He journeyed to Accra with his wives, secretary (the Muslim cleric) and cattle. He became very rich and prominent and attracted the attention of the Ga Manste, King Taki Tawia. He established himself as a prominent merchant and devout Muslim, building relationships with the local Ga community as well as Afro-Brazilian returnees of Yoruba origin who had settled in Jamestown. Over time, he would become a key figure in the burgeoning Zongo community.

Brimah’s influence goes on in present-day Accra, shaping the Yoruba people’s historical identity, particularly through his descendants, who have not forgotten their beginnings and proudly tell their past.

Memories from the bloodline

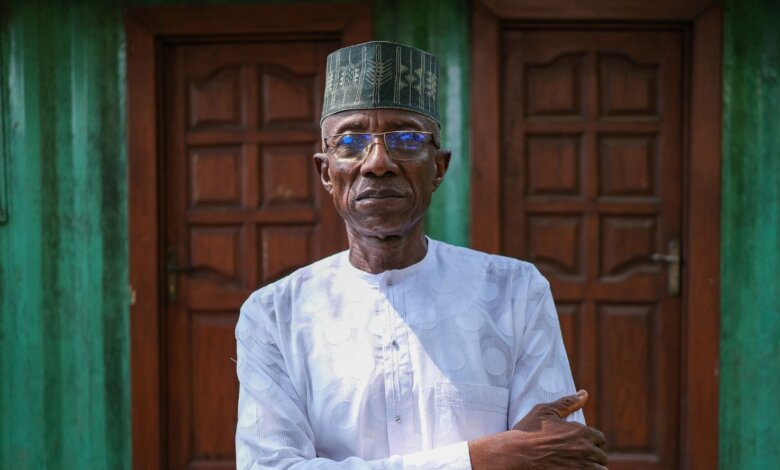

It’s a quiet late morning in Accra’s Nima suburbs, except for the occasional honking car that travels the same route that leads to Daily Guide, Ghana’s widely circulated private newspaper. The editor, Alhaji Abdulrahman Abdulhassan, a descendant and great-grandson of Chief Brimah I, the Yoruba trader who migrated from Ilorin to Accra over two centuries ago, sits in an average-sized editorial office behind his desk, which contains carefully arranged newspapers, books and a computer.

The coolness of the chamber provides relief from the hot Accra sun. He is wearing glasses, a Hausa headgear, and clothing akin to the northern Nigerian babanriga. He relates his history and his great-grandfather’s legacy with the ease and cadence of someone nurtured in several cultural worlds.

In another area of Accra, a 20-minute walk from Alhaji Abdulhassan’s office is Metro TV. Here, Bilikis Giwa, Chief Brimah’s great-granddaughter, recounts traditions passed down by her forefathers.

As inheritors of their great-grandfather, Chief Brimah’s centuries-long diasporic voyage, Alhaji Abdulrahman Abdulhassan and Bilikis Giwa both use their voices, viewpoints, and personal tales to bring to life a past that is frequently forgotten in discussions about Ghana’s and Nigeria’s cultural legacy. According to both descendants, Chief Brimah, whose name was a corruption of ‘Ibrahim’ was a native of Ilorin with Fulani and Yoruba ancestry.

He became one of the most influential Yoruba migrants to Accra. ‘The story we have in the family is that he was supporting a particular Emir. He was embroiled in a chieftaincy dispute and was supporting one faction against the other. So, he decided to leave with his wives, cattle and possessions in the early 1800s,’ Alhaji Abdulhassan narrated. ‘Eventually, he was told to head for a big ocean (the Atlantic) and he finally settled in Accra.’

Alhaji Abdulhassan added that:

“Chief Brimah was known as ‘Brimah the butcher’ and acted as a middleman for kola traders from Nigeria. He also married Fatima Opeidu, an indigenous Ga woman, cementing his ties with the local community. At the time kola nut was cultivated in both countries, but the variety grown in the Gold Coast (Ghana) was in high demand in Nigeria.”

The kola nut trade between the Gold Coast and Nigeria thrived due to the superior quality, distinct flavour and stronger stimulant properties of the cola nitida variety grown in the Ashanti region. They were highly sought after in Nigerian markets. For the Yorubas and Hausas, kola nuts were deeply embedded in cultural and religious practices. They served as an acceptable stimulant under Islamic norms and provided an alternative to alcohol, which was prohibited.

The caffeine-rich kola nuts were valued for their ability to increase alertness and endurance, making them a staple in social rituals, religious ceremonies and daily life. This high demand sustained a flourishing trade network, with Yoruba and Hausa traders transporting large quantities to Nigeria. This played a significant role in establishing a robust trade network, facilitated commerce and strengthened economic ties between the regions.

Trade and political realignment in the Gold Coast

Chief Brimah’s influence was intricately tied to the shifting political and economic dynamics of the Gold Coast, as he adeptly navigated the complexities of regional trade and colonial policies. His prominence in commerce allowed him to foster key alliances with both local leaders and colonial administrators and solidified his role as a central figure in the realignment of economic power towards Accra.

It would seem Chief Brimah’s migration to Accra was not the beginning of his journey as a trader, but rather the expansion of a thriving commercial career rooted in northern Ghana and Ilorin. Ilorin proved to be a strategic location at the crossroads of northern and southern Nigeria.

It provided access to vast trade networks, including the trans-Saharan routes that connected West Africa to North Africa and beyond. Oral histories and family accounts hint that Brimah was already deeply involved in the trade of cattle and other goods central to the regional economy. Perhaps this experience equipped him with the expertise and networks necessary to capitalize on larger opportunities.

“Brimah was a caravan trader, doing the trade from Ilorin to Salaga. It was a very long-distance trade that took a year,” Bilikis Giwa elaborated. “From Ilorin, he and other Yoruba and Hausa traders would move northward, passing through towns such as Gonja and Salaga in present-day Ghana.” These towns were important stops on the trading route, particularly Salaga, which was known for its thriving kola nut market. “Continuing southward, traders eventually reached the coast, where Accra emerged as an important destination,” she added.

Giwa went on, explaining that: “After the British took control of the Gold Coast from the Dutch and Danes in 1850 and 1872 respectively, they sought to consolidate their authority by weakening the Ashanti Kingdom’s resistance and dominance over regional trade.” Following their victory over the Ashantis, the British switched their economic attention to Accra, establishing it as the new colonial capital.

This planned manoeuvre was intended to divert business from Ashanti-controlled areas such as Salaga to Accra, while also centralizing power in Accra. Salaga had long been an important trading town under the Ashantis’ control due to its thriving kola nut market and significance in trans-Saharan trade. “The British knew the Ashantis derived much of their power from controlling trade routes,” Giwa pointed out. “By relocating commerce to Accra, they effectively quelled the Ashanti kingdom’s influence.”

As a result, Accra’s Salaga market emerged as a hub for trade and economic prosperity. The Salaga market has a deep and convoluted history as a significant slave traffic transit place. According to Giwa, ‘The sacred well at the market is a significant reminder of these intertwined histories of the legacy of those times.’ The move to divert trade from Salaga to Accra was an attempt to undermine the Ashantis’ power and centralize trade under colonial surveillance.

Forming Zongo communities

The influx of Hausa, Fulani and Yoruba peoples to Accra profoundly altered the city’s socio-cultural and economic landscape. As traders from northern West Africa arrived to participate in Accra’s thriving commerce, the need for communities customized to their specific demands became clear. This resulted in the formation of Zongo communities, which served as hubs for trade, cultural exchange, and religious activities.

Derived from the Hausa word for ‘stopover’ or ‘transit’, Zongo originally referred to transitory towns erected for traders and travellers. However, over time, these Zongos developed into permanent hubs—attracting a varied range of migrants, including Yoruba artisans, Hausa cattle ranchers and Fulani traders. Their shared Islamic faith and business ventures fostered a unified custom among the Zongos, allowing for multicultural interactions.

The founding of Zongos was strongly impacted by British colonial practices. The colonial administration categorized West Africa’s various peoples designating Muslim migrants as ‘strangers’ and separating them from indigenous groups like the Ga, Akan and Ewe. This segregation was part of a larger colonial policy of controlling various communities while profiting from their labour and economic contributions. The British categorized various locations as ‘stranger quarters’ or Zongos, where non-indigenous groups were concentrated.

These ‘strangers’ were referred to as the Mohammedans due to their common religious beliefs. This categorization method inadvertently increased Zongo communal relationships. While the British attempted to preserve order by delineating ethnic and socioeconomic divisions, these settlements evolved into self-sufficient cultural hubs where traditions survived. Over time, Zongos established their social systems, with mosques, markets and schools functioning as important organizations.

Chief Brimah played a prominent role in shaping the Zongo communities. Appointed by the Ga King, Tackie Tawiah I, as the head of the Mohammedan community, Brimah emerged as a unifying leader among the diverse ethnic groups in the Zongos. His leadership was marked by his ability to mediate disputes, foster trade networks, and uphold Islamic principles.

Despite his contributions, Brimah faced resistance from certain factions, particularly among the Hausa and Fulani communities, who found it challenging to accept a Yoruba leader. “He had problems with the Fulanis and others who didn’t want to recognize him as such,” Alhaji Abdulrahman Abdulhassan recounted, adding that:

They could not come to terms with a Yoruba man becoming their head. If you know the history of the Ilorin people, besides the Afonjas and the others, you will see that they are closer to the north than the Yorubas. They have a lot of Hausa culture. So, that they looked at Chief Brimah as Yoruba was not appropriate, even though he was from the Fulani quarter.

This resistance reached the colonial administration, which ultimately endorsed Brimah’s leadership, recognizing his significant role in maintaining order and cohesion within the Zongos.

Thus, Alhaji Abdulhassan noted that, “In 1909, matters got to the acting governor, Major Herbert Bryant, who when the leadership of the Zongo community went there, told them they could only endorse what had been said because this man was the appropriate head of the Islamic community.”

While Chief Brimah had been appointed to simply head of the Mohammedan and Zongo communities, Alhaji Abdulhassan explained that, “he eventually became head of the Islamic community in Accra and then later the Yoruba community. So, he was referred to as Chief Brimah the First.” This marked the beginning of an established Yoruba monarch in Ghana.

Alhaji Abdulhassan continued that, “Brimah was made the head of the Mohammedan community between 1908 and 1909 by the Ga King, but it didn’t take effect until the death of the Ga King. So, there was a coronation when the king passed on the king. At the time, the Muslim population in Accra was just about 5,500.”

Brimah’s leadership played a pivotal role in shaping the Zongo community in Accra. Recognized as a leader of the Mohammedans, he became a unifying figure and fostered collaboration among the diverse ethnic groups within the Zongo. His ability to mediate disputes, organize trade networks, and uphold Islamic principles modelled the integration of various cultural and religious traditions under a cohesive identity.

The British categorization of Zongos as distinct quarters also inadvertently strengthened their communal bonds. Though the Zongo settlers shared the same faith, each ethnicity retained autonomy and adhered to their cultural norms. This seclusion, albeit entrenched in colonial power, allowed the Zongos to maintain their own cultural and religious customs.

Zongos were also sites of great cultural synthesis. “Our Zongo communities were not just residential areas; they were melting pots where different cultures co-exist and thrived together,” Bilikis Giwa said, adding that:

Though I have Yoruba ancestry, I am a Ghanaian, and we have held onto our history up until today, traditions, and we intermarry, and the fact that we don’t even allow our people to marry other tribes, especially when the person is indigenously Ghanaian. So, at least, it has kept us going till today.

The fact that we’ve managed to keep our community together. We have our own Imam, our own Chief Brimah the IX, our Yoruba leader. So it should tell you how long we’ve been in Ghana, and how we’ve been able to maintain the community. Unfortunately, we do not retain authentic Yoruba traditions, but rather Yoruba traditions based on our Islamic religion.

The broader legacy of Chief Brimah

Chief Brimah’s family history includes connections to Afro-Brazilian returnees who settled along the West African coast. This is by virtue of his marriage to a member of the Peregrino family, one of the formerly enslaved Brazilian returnees of Yoruba descent known as the Taboms. An estimated 3,000-8,000 formerly enslaved Africans chose to return to Africa. When they arrived, they divided up along the shore, which is why the Brazilian returnees settled in Lagos, Togo, and Ghana.

The Tabom people were an Afro-Brazilian community that settled in Jamestown, Accra, in the 19C century. Known for their tailoring expertise, the Taboms helped create Accra’s cultural scene. Their moniker, taken from the Portuguese word tá bom (meaning ‘it’s okay’), refers to their initial interactions with the Ga people. Brimah’s leadership and relationships with communities such as the Tabom and the Ga boosted his family’s influence in Accra’s heterogeneous landscape.

The Homowo festival, an annual traditional celebration of the Ga people, is a notable example of such cultural impact. During Chief Brimah’s lifetime, his family provided the cow used for festival sacrifices. Although the nature of their contributions has changed, the Ga community continues to visit the Peregrino family every Homowo to show their support. This long-standing custom illustrates the shared history of the Ga, Afro-Brazilian and Yoruba populations.

Through the years, Accra drew more migrant traders. Yoruba families such as the Alawiye and Giwa clans were among the many migrant communities that thrived in Accra as a result of the city’s rapid development. These families, like the Brimah family, contributed significantly to Accra’s social and economic development. The Yorubas and the Alata subgroup of the Ga people have close historical ties, which contributes to this story of cultural convergence.

One prominent connection is the construction of Osu Castle, where Yorubas were imported from Nigeria to contribute their skills. After the castle was completed, several of these labourers remained, creating a legacy in the community. The ship that brought them, the SS Alata, became a cultural symbol, and some ethnic groups in Ghana still refer to Yorubas as ‘Alata’.

Accra’s history is still centered around the Brimah family. The founding of Lagos Town, later called Accra New Town, demonstrates that the family’s influence extended beyond cultural preservation to include urban development. Chief Brimah’s son, Abdelkadiri Brimah, helped to construct a prosperous Yoruba enclave through land acquisition and development. Despite the political conflicts that led to the renaming of Lagos Town, the community’s residents continue to use its former name.

Over time, Brimah’s descendants carried on his heritage. The Brimah dynasty remains dominant, with its current leader, Chief Hamza Peregrino-Brimah IX, serving as a first-class king and high chief, recognized as the Oba of all Yoruba descendants in Ghana. Giwa supports this influence by recalling that three years ago the annual Ishokan Yoruba festival was started as a way to keep the Yoruba community thriving and maintain cultural interaction and engagement.

A Ghanaian precursor to ‘Ghana must go’

By 1931, Ghana had attracted many immigrants from across Africa, with Nigerians as the dominant group drawn by Ghana’s economic prosperity in trade and agriculture. This influx birthed the 1969 Aliens Compliance Order issue that uprooted over a million Nigerians, including many Yoruba families, out of Ghana and became a precursor to Nigeria’s ‘Ghana Must Go’ crisis of 1983.

Economic constraints and political tensions were at the heart of this enormous expulsion—as Ghana struggled with a faltering economy and wanted to reclaim control of its resources and workforce. There was widespread resentment towards foreign immigrants, particularly Nigerians, who were perceived as dominating informal trade and other business sectors.

Unregistered immigrants who were allegedly ‘stealing jobs’ and business opportunities from Ghanaians during a period of economic distress were the primary targets of this order—which was purportedly intended to regulate the status of foreign nationals living in Ghana.

Yoruba migrants, many of whom had established themselves in critical economic hubs like Makola market, and other bustling trade centres, were disproportionately affected. Known for their entrepreneurial spirit, Yoruba traders dominated sections of the market. However, during the expulsion, these same thriving businesses were targeted. Shops were closed, goods were confiscated, and many Yorubas were forced to abandon properties they had invested in for decades.

This crisis left a lasting impression on the Yoruba community, and Nigerians at large. Perhaps, as a retaliation, the Nigerian government in 1983, under President Shehu Shagari, conducted a mass expulsion of undocumented immigrants, including Ghanaians. This event, known as ‘Ghana Must Go’, mirrored the earlier Ghanaian expulsion.

Over time, the scars of these expulsions have given way to renewed collaborations, trade and cultural exchanges, but the memories linger. Ghanaians and Yorubas have continued to communicate culturally and migrate despite the mutual deportations. This process was further facilitated by the creation of the Economic Community of West African States in 1975 and the administration of President Jerry Rawlings (1993-2001), which supported Yoruba business in Ghana.

Contemporary Yoruba migrants

In recent times, Yoruba migration to Ghana has taken a new shape. Unlike past migrations that were motivated by trade, political conflict, or religious expansion, modern migrations are frequently influenced by economic globalization, educational possibilities and the desire for improved living conditions. Perhaps, Accra’s status as one of West Africa’s fastest-growing urban centres, as well as its proximity as an Anglophone neighbour, has made it an appealing destination for a new generation of Yoruba migrants.

Many current migrants are young professionals, traders, and artisans who have discovered opportunities in Ghana’s reasonably stable economic environment. Furthermore, Ghana’s reputation as a peaceful and accessible Anglophone country in comparison to other parts of West Africa has encouraged Nigerians, mainly Yorubas, to relocate to towns like Accra, Kumasi and Tema. The existing Yoruba community and those whose families have been naturalized have made it a safe landing for new Yoruba migrants in search of greener pastures.

Nonetheless, for new Yoruba migrants, settling in Ghana offers chances and challenges. Historical relationships and cultural similarities with the Ga people may provide a sense of familiarity. Nevertheless, modern migration is influenced by economic competitiveness, legal barriers, and identity issues. Thus, the younger generation is forging hybrid identities, blending Yoruba traditions with Ghanaian and global influences, as a dynamic interplay between cultural adaptation and preservation.

One major challenge is reconciling Yoruba ancestry with the need to integrate into Ghanaian culture. Earlier generations retained traditions such as naming rites and marriage ceremonies, but today’s migrants face the risk of losing these customs when cultural transitions occur. This tension is especially obvious in urban areas like Accra, where the allure of cosmopolitan lifestyles and modern needs frequently clashes with the preservation of cultural traditions. The dilemma for new migrants is how to preserve their identity while succeeding in a fast-changing environment.

Economically, contemporary Yoruba migrants make major contributions to Accra’s trade and service sectors. Nigerian-owned enterprises, including eateries like Buka Restaurant, Mama Africa , shipping companies such as GIG,Topship and retail stores such as The Lotte Accra, Flutterwave, etc. have become essential components of the metropolitan scene.

These enterprises serve not only the rising Nigerian diaspora but also Ghanaians who value Nigerian products and food. Yoruba artisans and entrepreneurs continue to succeed in fields such as fashion, boxing and music, with the introduction of Nigerian films and Afrobeats to Ghana generating cross-border appreciation and collaboration.

However, migrants still navigate perceptions of economic competition and occasional hostility. These challenges show the complexity of migration narratives, where economic opportunity coexists with social friction. Yet, the perseverance and contributions of Yoruba migrants disclose the potential of migration to shape and redefine cultural and economic landscapes in West Africa.

Source: The Republic

This article is published by either a staff writer, an intern, or an editor of TheAfricanDream.net, based on editorial discretion.