The Art of Ghana

Interest in art from Africa has never been stronger. Auction prices are escalating; the continent’s art is increasingly visible in museums in Europe and especially in the US, where institutions are striving to appeal to their African-American constituencies.

A dedicated fair, 1:54, was launched in London in 2013, and last year added a New York edition to its roster.

In Africa, though, the picture is less rosy. Public funding is scarce. With the exception of South Africa and Nigeria, there are almost no commercial galleries to sell artists’ work and provide them with a livelihood. Despite the global appetite for African art, emerging talent does not have it easy.

If any country encapsulates that contradiction, it is Ghana. The west African state provides no public funding for contemporary art and has only a tiny commercial sector. Yet it has a vigorous arts scene and is the homeland of international favourites El Anatsui and Ibrahim Mahama.

Gallery 1957, Accra’s first commercial gallery for contemporary art, opened in March. Taking its name from the year of Ghana’s independence, it is already providing an important platform for artists who have hitherto had to rely mostly on cultural spaces funded by foreign embassies and independently run foundations to show their art. Last week saw the opening of its second exhibition, devoted to work by Zohra Opoku.

The artist, now 40, was raised by her grandparents in Germany, and moved to Accra five years ago to discover the heritage of her Ghanaian father. In Ghana, her work has included the installation on public billboards of second-hand clothing imported in bulk from the west for a project exploring global inequality and the trade in discarded garments.

At the opening of her show, she performed capoeira, the Brazilian-African martial art, in front of a video of herself doing the same moves which was screened outside the gallery. Inside the displays include screen-prints on textiles showing portraits of the artist submerged in foliage.

“One of the main reasons we started Gallery 1957 was to support Ghanaian artists like Zohra so they can live, work and sell their art here,” says British-Lebanese construction entrepreneur Marwan Zakhem, who set up the gallery in the Kempinski Hotel Gold Coast City.

Traditionally many African artists have had to leave their native countries to pursue their careers. A case in point is Anatsui, whose installation of shimmering curtains made from recycled materials such as soda cans, priced at $3.8m, has proved a crowd-pleaser at Art Basel this week.

Now aged 72, Anatsui left Ghana long ago for Nigeria, a country with a more developed art market. But a new generation of artists is choosing to live and work in its native country. This is made possible not just by the growing global cachet of African art, but also by the rise of social media, which provide artists with the means to promote their work overseas without leaving home.

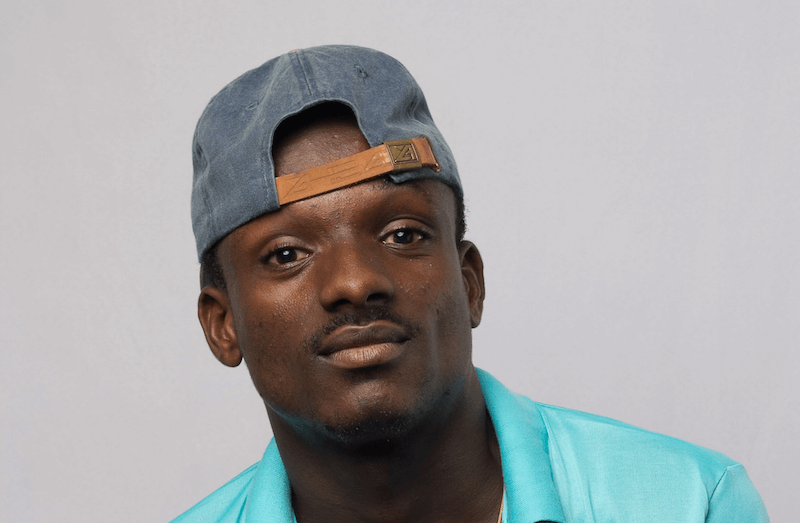

One of this group’s most prominent members is Mahama, a fast-rising star of African art. “It’s very important not to leave Ghana,” he says. “You want to feel 30 years from now that you were part of the struggle, that you have helped to build this country.”

The 28-year-old attracted attention at the Venice Biennale last year with a 300-metre installation constructed from the jute sacks used to transport food and coal in Ghana. Upcoming projects include exhibitions at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art in December, the National Museum of African Art in Washington DC next year as well as White Cube in London in February (the gallery has declined to say whether Mahama is joining its stable of artists).

Back home in Ghana, however, Mahama has had to organise his own displays. He has draped his trademark jute-sack installations over public buildings such as apartment complexes, universities, and the National Theatre, funding the production of his own work and instigating negotiations with the relevant authorities. But he is philosophical about the lack of institutional support. “[It] does not mean that we can’t still make art,” he says. “Art precedes the White Cube or any other space.”

Their commitment is shared by Serge Attukwei Clottey, another standout local talent. “My work is about my community, and I want to stay here to help build that community up,” he says. Attukwei Clottey makes murals from fragments of the yellow plastic containers used to transport water in Accra, a symbol of the enduring water shortages in the city and the failure of successive governments to fix the problem.

The artist inaugurated Gallery 1957 with My Mother’s Wardrobe, an exhibition of his wall pieces (priced between $5,000 and $35,000) and a performance.

Attukwei Clottey and the members of his community theatre troupe, GoLokal, dressed up in their mothers’ clothing and walked in procession from the artist’s studio in the La neighbourhood in east Accra, with its makeshift housing and dirt roads, to the marble-clad interiors of the Kempinski Hotel in a performance that explored issues of gender identity and sexual politics.

“Gay and transgender issues are very hidden here in Ghana,” he says. “It’s considered very bad to be gay. After travelling in the US and Europe, I came to understand that it’s a human right to express your identity.”

Like many artists in Ghana, Attukwei Clottey trained as a painter and spent years selling his canvases to fund his other projects. But now, he says, “Gallery 1957 is making a strong impact, supporting artists and their production. It’s what we need to focus on making art.”

Nana Oforiatta Ayim, the writer, filmmaker and curator who is the creative director of Gallery 1957, moved back to Accra from London five years ago to help support artists such as Attukwei Clottey and Mahama.

“I wanted to make it possible for artists to be here without having to travel to Europe to make art,” she says.

She also runs a foundation for artists, ANO, and is organising a public performance by Attukwei Clottey on a lagoon in Accra in October.

“I hope there’s enough of a market in Ghana for this kind of art and that people start buying it here,” says Zakhem. But the country’s biggest art collector, Seth Dei, co-founder of fruit-processing company Blue Skies, has his doubts. “There was nobody buying art when I started and there are very few people buying it now.” This, he says, will make it difficult for new events such as Art Accra, an art fair launching at La Palm Royal Beach Hotel in the city in December. Yet Dei is optimistic because young artists today are “not afraid to take risks. And courage is one of the keys to creating great art.”

Much of that courage has been instilled by the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology in Kumasi, which is home to one of the best art schools in Africa. The school’s graduates include Anatsui and Mahama, who attributes much of his success to the school. “We turn the lack of any state support or institutions in Ghana into an advantage. We tell our students that their exhibition space is the whole of Ghana,” says lecturer Kwaku Kissiedu.

This enterprising spirit is epitomised by Accra’s annual Chale Wote street art festival, which is part celebration, part protest and entirely self-funded. Its co-founder Mantse Aryeequaye believes that art has a critical role to play in holding the powerful to account. “We are dealing with so many different issues here and there is so much work to be done. Your only weapon to fight back against a system that oppresses you is your art.”

Every artist that matters in Ghana now believes it is his or her responsibility to deal with such issues.

“I believe artists can help shape the future,” says Mahama.

‘Zohra Opoku: Sassa’ is at Gallery 1957, Accra, until August 10, gallery1957.com

The Chale Wote street art festival is in James Town, Accra, August 18-21

Photographs: Gallery 1957

Source: FT.com