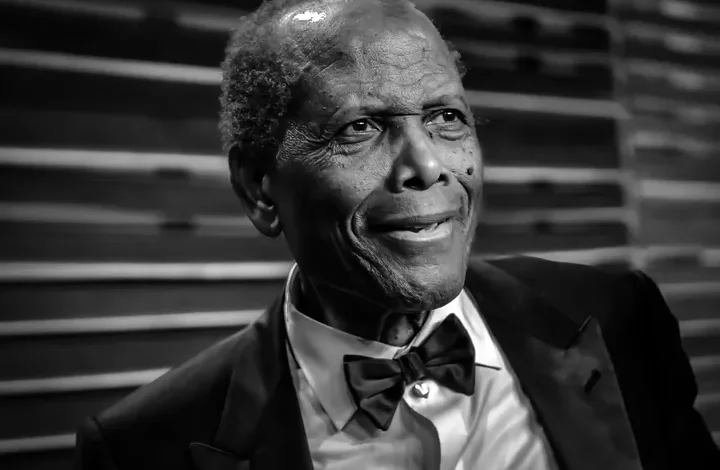

A Profile on Legendary Sidney Poitier 1927-2022

Sidney Poitier, the Bahamian-American actor who broke countless Hollywood barriers in the 1950s and 1960s, most notably in 1964 when he became the first Black man to win an Academy Award for best actor, has died.

This was according to Bahamian news reports citing the country’s foreign affairs minister. He was 94 years old at the time.

Poitier was frequently the “first” throughout his career. In 1957, he was the first Black man to win an international film prize at the Venice Film Festival; in 1958, he was the first Black man to be nominated for Best Actor at the Academy Awards; and, of course, he was the first Black man to win it for “Lilies of the Field.”

“I had a sense of responsibility not only to myself and to my time, but certainly to the people I represented. So I was charged with a responsibility to represent them in ways that they would see and say, ‘OK, I like that.'”

– Sidney Poitier (2008)

“Sidney Poitier does not make movies, he makes milestones,” The New York Times’ Vincent Canby stated in a 1969 review of Poitier’s film “The Lost Man.” Canby intended the statement as a dig at Poitier, who continued to work with “second-rate directors,” as Canby put it. But it was also an unmistakable homage to the extensive list of firsts that had become synonymous with Poitier’s name by that point.

When President Barack Obama awarded Poitier the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2009, he quoted the line, complimenting the actor’s efforts:

“Milestones of artistic excellence, milestones of America’s progress… Poitier not only entertained but enlightened… Shifting attitudes, broadening hearts, revealing the power of the silver screen to bring us closer together.”

Poitier pushed against the typical roles of Black men in Hollywood. In 1961’s “Paris Blues,” he played the first Black romantic lead in a major picture. Together with Katharine Houghton, he portrayed the first positive depiction of an interracial couple in a major Hollywood film with 1967’s “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner.”

In 1968, he became the first Black man to be named Hollywood’s top box office star. In 1975, he appeared in the first film to take a stance against apartheid, “The Wilby Conspiracy.” And for 1969’s “The Lost Man,” he demanded that at least half of the film crew be Black, the first time such a thing had ever been done.

His advocacy was not limited to the screen. He was there for Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s historic “I Have A Dream” address at the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963. Poitier returned to D.C. in 1968 to support the Poor People’s Campaign, which King had organised in part before his assassination.

No less than Dr. King himself celebrated Poitier’s contributions to society, saying of the actor in 1967, “He is a man of great depth, a man of great social concern, a man who is dedicated to human rights and freedom.”

Despite his achievements in his own business during the Jim Crow era, Poitier was falsely accused by some of choosing safe roles that made white people feel comfortable over roles that directly tackled racial discrimination.

Read Also: South African Anti-apartheid Archbishop Dead at 90

“There was more than a little dissatisfaction rising up against me in certain corners of the black community,” Poitier wrote in his 2000 autobiography, “The Measure of a Man.” “The issue boiled down to why I wasn’t more angry and confrontational. New voices were speaking for African-Americans, and in new ways.

Stokely Carmichael, H. Rap Brown, the Black Panthers. According to a certain taste that was coming into ascendancy at the time, I was an ‘Uncle Tom,’ even a ‘house Negro,’ for playing roles that were non-threatening to white audiences, for playing the ‘noble Negro’ who fulfills white liberal fantasies.”

“He just wasn’t of those times,” said Al Young, a scriptwriter who briefly worked with Poitier in the 1970s. “His was an era of polite gentlemanly etiquette. Hollywood was warming to blaxploitation movies like ‘Shaft.’ I remember going to his house in 1976, and Sidney and his wife left me in the garden.

I sat down on the grass and started reading a copy of Rolling Stone magazine ― I was a writer for them. Suddenly, the upstairs window opened and there was Sidney. ‘Al,’ he exclaimed. ‘What are you doing?’ I told him I was sitting on the grass. ‘But we never do that!’ he yelled. ‘My God! Can I get you a chair?’”

In fact, there was something stirring in Poitier in those days. But only later, in his autobiography, would Poitier reveal the anger he fought to keep hidden during the early years of his career. “I’ve learned that I must find positive outlets for anger or it will destroy me,” he wrote.

“There is a certain anger: it reaches such intensity that to express it fully would require homicidal rage ― it’s self-destructive, destroy-the-world rage ― and its flame burns because the world is so unjust. I have to try to find a way to channel that anger to the positive, and the highest positive is forgiveness.”

Poitier was born two and a half months early, on February 20, 1927, in Miami, Florida, where his Bahamian parents were on vacation. Poitier grew up poor, the youngest of seven children. Poitier’s father was a tomato farmer, and by the time he was 13, he was working full-time to help support his family.

His family chose to put him on a boat to the United States to seek a better life after only two years. “Take care of yourself, son,” Poitier’s father told a young Sidney Poitier.

Later, Poitier would remember looking back at his father from the boat and say, “He was thinking about whether he and my mother had given me enough before I had to go out into the world. And I think now that they did. He gave me infinitely more than the three dollars he put in my hand.”In Florida, Poitier was introduced to a type of racism that he had never before experienced, and that he had no plans to adhere to.

He later told Oprah, “The law said, ‘You cannot work here, live here, go to school here, shop here.’ And I said, ‘Why can’t I?’ And everything around me said, ‘Because of who you are.’ And I thought, I’m a 15-year-old kid — and who I am is really terrific!”

Poitier arrived in New York City at the age of 16, where he lied about his age in order to join the army during World War II. He found work as a dishwasher when he returned. Then something happened one day:

“I was at 125th Street [in Manhattan], actually, looking in the newspaper for a dishwashing job. And there were none,” he later told Larry King. “I began to fold the paper and put it into the street bin for trash and something on the opposite page caught my eye. And what caught my eye was two words ― ‘actors wanted.’”

The American Negro Theatre wanted actors, and Poitier wanted to try out. But with no acting experience and a thick Bahamian accent, the audition went horribly, so much so that he was told, “Stop wasting your time — get a job as a dishwasher!” Half a year later, he tried out again, this time successfully, earning a role in a play called “Days of Our Youth.” He was filling in for Harry Belafonte, a man who would become one of his lifelong friends.

From there, his career blossomed ― and fast. By the time he was 19, in 1946, he was on Broadway in the all-black production of “Lysistrata.” By the time he was 23, he had made it to Hollywood with the 1950 noir film “No Way Out.”

Even at his peak, despite the criticism he received later in his career, Poitier’s life was not always simple. The award’s presenter, Ann Bancroft, gave him a little kiss on the cheek when he won the Oscar for best actor in 1964, causing a stir at a time when anti-miscegenation laws were still in effect in many states, making it illegal for a Black man and a white woman to marry.

In the 1967 film “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner,” he shared Hollywood’s first-ever interracial kiss with Katharine Houghton.

Poitier received numerous awards in his later years, including an honorary Oscar in 2001 and the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2009. He was appointed as the Bahamas’ ambassador to Japan in 1997. However, he appeared to be more interested with improving the lives of those around him, as well as those who watched him on television, than with receiving plaudits.

Beverly, Pamela, Sherri, Anika, and Sydney Tamiia, Poitier’s wife, Joanna Shimkus, and five of his six children, Beverly, Pamela, Sherri, Anika, and Sydney Tamiia, survive him. Gina Poitier, his daughter, died in 2018.

Source: HuffPost

Abeeb Lekan Sodiq is a Managing Editor & Writer at theafricandream.net. He is as well a Graphics Designer and also known as Arakunrin Lekan.